Biodiversity Action Agenda

To download a PDF copy of the Biodiversity Action Agenda, click on the links below. To view the web version, scroll down.

This action agenda represents the majority of views shared through the 4-part conversation series by the authors listed below. Click here to view the expert panel contributors and their affiliations.

Ann Dale; Leslie King; Valerie Behan-Pelletier; Dawn Bazely; Meg Beckel; Dawn Carr; Holly Clermont; Jaime Clifton-Ross; Michelle Corsi; Susan Eaton; Eleanor Fast; Susan Gosling; Jodi Joy; Brenda Kenny; Elizabeth Kilvert; Patricia Koval; Christine Leduc; Nina-Marie Lister; Anne Murray; Sarah Otto; Laren Stadelman; Susan Tanner, and Sharolyn Mathieu Vettese

Canada prides itself on being a welcoming nation and a model for multiculturalism. We congratulate ourselves on our ability to include people from around the world into a society that appears to value difference. Yet respect for cultural diversity is still evolving in modern society, while values for biological diversity are lagging far behind. Although we value our iconic emblems—the polar bear and the loon—these species and their habitat are now under threat. Canada’s natural spaces are a vital component of our culture, heritage, economy and our future, and are of global importance. Canada’s forest, wetlands, prairies, tundra and oceans provide essential ecosystem services. Approximately 30% of the world’s boreal forest, 20% of the world’s freshwater resources, the world’s longest coastline and one of the world’s largest marine territories are ours to enjoy, protect and share1.

There is no doubt that biodiversity loss is accelerating at an alarming rate, both domestically (WWF Living Planet Report Canada, 2017) and internationally (WWF, ZSL, 2014), with the number of all wild animals declining by 50% in the last 40 years. The abundance of flying insects has dropped by three-quarters over the last 25 years. Over one in five species of vertebrates (Hoffman et al., 2010), invertebrates (Collen et al. 2012), and plants (Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, 2010) are at risk of extinction. A “biological annihilation” of wildlife in recent decades indicates that a sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history is under way and is more severe than previously feared (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2017). This mass extinction of global wildlife already is provoking cascading effects on food webs, jeopardizing ecosystem services as well as threatening the world’s food supplies (Biodiversity International, 2017).

The biodiversity imperative is different from other social challenges and we would argue is even more critical than, although certainly related to, climate change. Why? There is no recovery from extinction, it is forever and unlike climate change whose impacts will be felt by many of the world’s population in the future, biodiversity loss is here now in the present, there is no future discounting.

We believe that it is crucial that Canada act now based on this evidence. We present this action agenda to all Canadians and decision-makers in particular, asking all to boldly implement the recommendations. We offer a combination of actions, including low-hanging fruit as well as deeper, longer term and essential systemic changes that we believe will unlock the potential to reverse biodiversity loss and associated local to global environmental threats.

[1] All references in this text are drawn from the expert panelists and all sources are in the curated biodiversity resource library.

For these reasons, we convened a series of real-time on-line virtual conversations that brought together experts from all sectors—business, academic, government and civil society to discuss and deliberate on the challenge of biodiversity loss and viable solutions. The conversation series was led by Royal Roads University in partnership with Women for Nature, Nature Canada.

By convening over 20 members of Women for Nature, mobilized by the evidence above, we collectively identified and discussed strategies to help inform decision-makers as well as the Canadian public. An unanticipated outcome was the wealth of information and references brought forward by the expert panelists, which are curated in a biodiversity conservation resource library that is now available for the general public. Click the button below to explore articles, videos, artworks, and more!

The series was publicized extensively by both partners using diverse social media channels. Over 157 real-time e-audience members participated, and the website received over 12,567 pageviews throughout the 8-month period of the series. Webpages promoting the series on Changing the Conversation were visited by 5,273 users. A total of 7,821 e-blasts were opened, 30,502 users were reached on Facebook, and tweets received a total of 105,289 impressions.

The 4 conversations from the series, How Important are the Common Loon and Polar Bear to Canadians, are archived below:

What is Biodiveristy and Why is it Important? Panelists began with a broader discussion on the nature of biodiversity conservation, before moving into more specific issues. They explored the critical relationship between human well-being and biodiversity, focusing on diversity as a general theme, as well as the current state of biodiversity loss in Canada. They discussed why it is imperative for Canada now, looking at the 2016 Living Planet Report, the state of North America’s Birds 2016 and the connection between biodiversity conservation and regenerative sustainability.

What is Biodiveristy and Why is it Important? Panelists began with a broader discussion on the nature of biodiversity conservation, before moving into more specific issues. They explored the critical relationship between human well-being and biodiversity, focusing on diversity as a general theme, as well as the current state of biodiversity loss in Canada. They discussed why it is imperative for Canada now, looking at the 2016 Living Planet Report, the state of North America’s Birds 2016 and the connection between biodiversity conservation and regenerative sustainability.

From the Local to the Global This conversation used the monarch butterfly to illuminate the local to global interdependencies of biodiversity conservation. Panelists revealed the dynamic interconnections and the need for global governance systems essential to protecting critical habitats and migratory paths. Biodiversity, like climate change, does not respect political borders and requires a broader systems approach for its conservation.

Drivers and Barriers This conversation focused on the drivers and barriers to the national, regional and local resolution of biodiversity conservation as biodiversity conservation is an issue that requires work from multiple scales. Panelists also explored what Canadians can do in their day to day lives to help protect and preserve biodiversity, individually and collectively.

Where Do We Go From Here? This conversation brought forward recommendations from the previous three to develop more concrete on-the-ground actions. Following this conversation, an action agenda sharing ideas from the 40 e-panelists and e-audience members will be released in September 2018 for Canadian decision-makers in all sectors. Imagine if we design with biodiversity in mind, the possibilities that would open up.

The three critical drivers augmenting biodiversity loss are our disconnected relationship to the land, over consumption and habitat loss. Although much progress has been made in the last few years, still only 10.5% of terrestrial and 7.7% of marine areas are formally protected in Canada, leaving most of its nature vulnerable to rapid degradation. We have yet to reach the IUCN’s previous target of 12% conserved and protected lands; and worse, we are now the last of the original signatory parties to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro and the Biodiversity Convention to begin to approach 17% (a far cry from the metaphorical Nature Needs Half movement).

Our governance systems are linear and fragmented, institutionally and jurisdictionally2; they still reflect a dominant and profound belief that nature and culture are hierarchically divided. This binary approach is manifest most clearly in how we appreciate, evaluate and ultimately protect and exploit biodiversity—the cleavages between urban and peripheral, rural regions is every bit as profound as the approaches to conservation.

Without solutions—obvious, attainable ones—any policy is doomed to failure. Just as there is a time imperative for conserving biodiversity now, we are ‘stuck’ in inaction by politicians bound by a system that is capable of thinking only in terms of electoral time. So, the question is, how do we get this call to action front and centre on political agendas of our local, provincial and national governments?

[2] For example, having industrial permits separate from the species protection act; considering projects in insolation rather than their cumulative effects; addressing climate change and biodiversity separately.

A key theme raised in our discussions was the importance of design (places and policies) for landscape connectivity, as it is key to sustained long-term conservation. Smart evidence-based ecological design is economical as well as effective; human-designed green infrastructure connects, protects and reveals the importance of biodiversity. For example, essential landscape connections within, through and around urban regions facilitate wildlife movement, breeding, feeding and access to habitat. These connections can be reframed effectively as infrastructural investments. Connected landscapes rely on green infrastructure in the form of wildlife passages, corridors, overpasses and underpasses, which are arguably as important as the “grey” civil engineered infrastructure that defines our cities. Understanding green infrastructure connections as essential to biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, as well as human well-being is an important way to reframe our capital investments (UNEP 2017).

One of the major barriers is the will to act—at all scales from our individual homes and gardens, to our workplaces and schools, to every level of governments. Unfortunately, we have a political system where “the urgent always gets in the way of the important”. The two major drivers working against biodiversity conservation are overconsumption and overpopulation. And alarmingly, very recent research has shown that biodiversity issues were largely sidelined by climate concerns; biodiversity was portrayed as being affected by climate change rather than as itself being pivotal to human wellbeing and essential to climate adaptation (Clermont, 2018).

Diversity and community resilience are linked—the survival of other species is integral to our own. For example, biodiversity provides many of our medical drugs, for example, the Madagascar rosy periwinkle is a plant from which we derive Vincristine, one of the key cancer fighting drugs in use today. 20 to 25% of drugs used in modern medicine are derived from plant chemicals and over 12,000 active compounds from medicinal plants are known to science. Three-quarters of the world’s food today comes from just 12 crops and five animal species, a very unsustainable path. Our biodiverse forests, soils, wetlands and prairies clean our air and water, sequester carbon, provide habitat for pollinators and keep pests and disease in check (http://www.landstewardship.org/ecological-goods-and-services/). Thus, a biodiverse world provides a critical resiliency guarding against failure in any one system.

Communications and education were also discussed extensively. Lessons can be taken from other cases, such as the ozone hole, or more recently plastics, where the public has been galvanized to act. With ozone, for example, the hole was visualized through videos and metaphors. An abstract atmospheric problem was reduced to the size of the human imagination. It had been made just small enough, and just large enough, to break through (New York Times magazine, Special Edition, The Lost Planet, 2018).

Reconciliation with First Nations, Inuit and Metis governments, nations, and peoples is tied intimately to the reconciliation of personal, ecological, social and economic imperatives that are essential for Canada to successfully respond to our current biodiversity deficit and loss. The current acceleration of human use and misuse of lands and water at the expense of nature, cultural diversity and biodiversity will continue unless new forms of community engagement and integrated planning are implemented. New models of collaborative leadership rather than competitive elected electioneering are urgently needed to implement this action agenda, and to close the knowledge-to-action gaps.

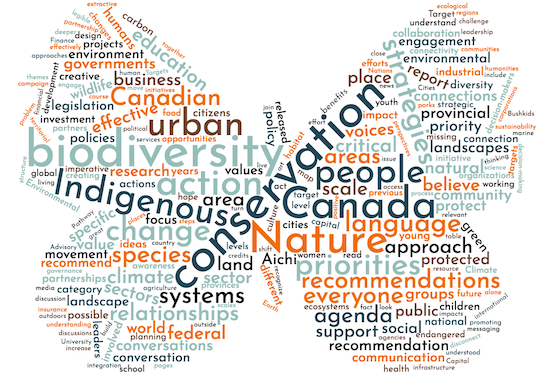

We must begin by diversifying the voices at every table moving far beyond the ‘usual suspects’. #Time is of the essence.

|

|

Ensure large landscape connectivity. The key to biodiversity conservation and regeneration is connection—between wildlife, people, agencies and place, and networks—to ensure large landscape connectivity so essential for biodiversity access to abundant and not merely adequate habitat. |

|

|

Many Indigenous Peoples in Canada share worldviews that the natural world is not separate from humans, but is a place where all living beings and spirits are connected. The principle of natural laws (ICE Report, 2018) offers an important pathway to (re)connect all Canadians to the land and the need to protect habitats, cultural and biological diversity. This highlights the importance of collaboration and partnership with Indigenous systems at all levels. |

|

|

Canadian governments at all levels must identify concrete conservation targets and priorities at local, regional and national scales through a process of bottom-up community participation and national-level identification of priorities to ensure local area-based conservation, and overall integration. |

|

|

Working in partnership with industry associations and opinion leaders in ESG (environmental, social and governance performance of public companies), inform the financial sector that, in their ESG analysis, there are significant benefits to integrating natural capital assessments into investment, lending and insurance decisions. |

|

|

Biodiversity strategies must be based on the Biophilic Cities movement of “nature-full” cities and take on an urban focus that speaks to new Canadians, millennials and the growing number of urban dwellers. |

|

|

Illuminate the co-benefits of integrated planning and inclusion of biodiversity plans in Official Community Plans, Integrated Community Sustainability Plans as well as Disaster Management Planning. |

|

Curate museum and art gallery collections outside of museum walls (Photo Ark), inclusive of Indigenous projects (clam gardens in BC) that promote and educate about biodiversity. Share the challenges biodiversity conservation is facing and the opportunities to protect it through public art and community engagement events. |

|

|

Nationalize the bioblitz models developed by the Royal Ontario Museum, Nature Canada and BioBlitz Canada 150, ideally led by Nature Canada, in partnership with other organizations working locally across Canada3. |

|

Launch a nationwide proactive communication campaign to increase civic literacy and action about biodiversity conservation. Develop short action briefs on key issues using easy to understand language (grade 5 reading level) with specific examples of impacts on humans of biodiversity loss with suggested actions using a variety of social media channels. |

|

(Re) position conservation as an urban initiative and challenge. Develop communication, language and strategic collaborations and partnerships as well as policies focused on the urban population for support, engagement, education and ultimately valuing and protecting biodiversity. |

|

Build and connect on success projects such as the National Geographic Ark project, Serengeti of the Arctic, Students on Ice, Earth Rangers and Canadian Wildlife Federation Species at Risk project. |

|

|

Make sustained funding and enforcement commitments to the implementation of both federal and provincial endangered species legislation. |

|

|

Invest in evidence-based conservation strategies that includes traditional ecological knowledge for migratory species; large-scale, ecosystem-based and connectivity planning initiatives in marine, aquatic and terrestrial environments. |

|

|

Establish a larger network of interconnected parks and marine protected areas which includes wildlife corridors. |

|

|

Enforce the Migratory Bird Act, and prosecute and fine companies, organizations and individuals whose activities negatively impact migratory birds. |

|

|

Implement and enforce Canada’s Species at Risk Legislation (SARA). |

|

|

Require connectivity mapping and hotspot identification be integrated into Official Community Plans and Land and Resource Management Plans. |

|

|

Implement a conservation credit system to encourage land-owners to protect biodiversity hotspots and ecological connections, as well as biodiversity offsets. |

|

|

Re-frame the issue from the traditional ‘humans apart from nature’ to ‘humans and biodiversity conservation’ as a key climate solution. |

|

|

Build on Indigenous worldviews and relationships with the land to offer new collaborative opportunities for affirming and effective conservation strategies, plans, communications and dialogue. |

|

|

Lead in sharply accelerating international dialogue on biodiversity, expanding upon the International Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and drawing on Canada’s expertise in round tables. This will help to include critical voices to the table beyond the usual scientific community—including museum scientists, research curators, communicators, visual and performing artists, the humanities, traditional ecological knowledge, in addition to the social sciences and natural sciences. |

|

|

Map Canada’s critical habitats for endangered and extirpated species and make this information publicly available to Canadians. It is critically important to identify areas requiring remediation. Include these priority areas included in local, regional and national plans. |

|

|

Lead the national implementation of the 20 AICHI Targets from the Convention on Biological Diversity, with clear timelines, by establishing a high level multi-stakeholder task force reporting to the Prime Minister, moving beyond the usual suspects. |

|

|

Ensure that the 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets for Canada are met or, better, exceeded, particularly Target 1. By 2020, at least 17 percent of terrestrial areas and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas should be conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. |

Collen, B., M. Bohm, M. Kemp, and R. Baillie. 2012. Spineless: status and trends of the world’s invertebrates. Report. London: Zoological Society of London

Hoffmann, M., C. Hilton-Taylor, A. Angulo, M. Bohm and T. Books et al. 2010. The impact of conservation on the status of the world’s vertebrates. Science, doi: 10.1126/science.1194442

The Indigenous Circle of Experts’ Reports and Recommendations. 2018. We Rise Together. Achieving Pathway to Canada Target 1 through the creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the spirit and practice of reconciliation

Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. 2010. Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31 March. London: The Stationery Office

Masood, E. 2018. Battle over Biodiversity. An ideological clash could undermine a crucial assessment of the world’s disappearing plant and Animal Life. Nature, 560: 423-425